Under Milei, Rural Feminists Fight for Rights and Resources

A feminist community radio station in Argentina has changed rural women's lives, but right-wing government threatens its existence.

Corrientes, Argentina—Estela Maris Ojeda leaned over a hardy harvest table, rummaging through a cardboard box filled with transparent bags of beautiful loot: beet, bean, butter lettuce, pea, and chicory seeds, all for crops that she tends to on the verdant plot of land she inherited from her parents in the arid Argentine province of Corrientes.

“I learned very young that everything is born out of this—seeds,” said Ojeda , a grandmother who hosts a seed exchange several times a year with fellow farmers.

It’s an important part of her grassroots activism, a way of fostering self sufficiency among rural women and creating a closeness to the earth, regardless of agricultural experience. And now, it’s more necessary than ever in an era of precarity for feminist activism in Argentina.

The feminist movement in the second largest country of South America has distinguished itself as being loud and proud. Massive demonstrations that filled the streets of Argentina’s biggest cities helped clinch huge victories, such as the 2020 legalization of abortion for cases up to 14 weeks of pregnancy.

But the landscape has changed under libertarian President Javier Milei, who has put the chainsaw he campaigned with into action, cutting roughly 30% of government spending in his first year in office. Along the way, he has deployed increasingly hostile rhetoric against the feminist movement, characterizing legal abortion as “aggravated murder” in public speeches, and denigrating so-called “woke” policies in an echo of his counterpart President Donald Trump in the United States. Milei’s government has used the power of funding to put that rhetoric into action, cutting financing for contraceptives and ceasing to provide abortion pills. Prior to his administration, the national government bought and delivered misoprostol and mifepristone to provinces that administered it free of cost through the public healthcare system. Now, that responsibility has shifted to provincial governments. The result, according to Amnesty International, has been shortages of medication in various provinces, hindering women’s ability to access a service that remains legal.

Away from the capital city, feminism in Argentina has always been a more complex undertaking, one that often exists in a conservative or religious environment where traditional gender norms hold firm. In more rural areas, women have found empowerment and support through small collective organizations that have planted seeds of activism in people like Ojeda.

Organizations like La Chicharra—the Cicada—a tiny community run radio station that is at the center of feminist organizing in Goya, the second largest city in Corrientes. The grassroots feminist project helped Ojeda find her voice, in part through workshops built to educate women on their rights, how to assert their worth in the home, and strengthening their financial autonomy.

“You end up thinking, if I leave my home, where am I going to go? Who is going to protect me?” said Ojeda, who lived through a period of violence with an ex-partner before returning to the farmland where she now lives and works. “What I learned in those workshops set me on a path to stop being afraid, for the benefit of me and my children. I realized a woman can go out on her own.”

The project traces its roots back to the Corrientes countryside and a small group of indigenous Guaraní women who gathered at community outposts to talk about the problems they confronted, and the challenges they solved. Community organizers trained the women on how to be mass communicators and turned their meetings into a radio program that they recorded with the analog technology of the time. Their program, called “Sapucai,” or scream in the Guaraní language, aired on an important local radio station.

“It’s women who get together, who talk about what they are going through, what they have suffered,” said Eladia Fernández, an arts teacher and former farm worker in Goya. “It gave us a sense of identity, telling stories about who we are makes you reflect on who we are.”

The program ended, but others grew in its place and people like Ojeda became regular contributors.

“We always knew that we needed to make the rural areas and the more marginalized neighborhoods more visible,” said Esther Migueles, a retired teacher and founding member of La Chicharra.

I realized a woman can go out on her own.

La Chicharra extended beyond the radio waves. It set up an itinerant “gender studies” school that traveled to tiny communities around Goya, holding the workshops that helped propel women like Ojeda to change the course of their lives. A sense of place was as important as a sense of purpose, said Cintia Coria, a member of the radio station and the school.

Milei’s decision to shutter the Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversities, the government agency responsible for addressing gender equality, has also dried up funding for education initiatives. The radio still operates, but on a shoestring budget. To cover costs, La Chicharra now relies on public donations, raffles, and other types of fundraising, such as bake sales. Under Milei, the deregulation of services such as the internet and the elimination of subsidies for utilities has also sent monthly bills skyrocketing, even as he has managed to dramatically slow down the rate of inflation.

“They are collective spaces that are very necessary, especially in the context that we’re living through now,” Coria said of the school. “When it comes to policies around gender, around women, and diversities, we’ve regressed in a way that I couldn’t even imagine.”

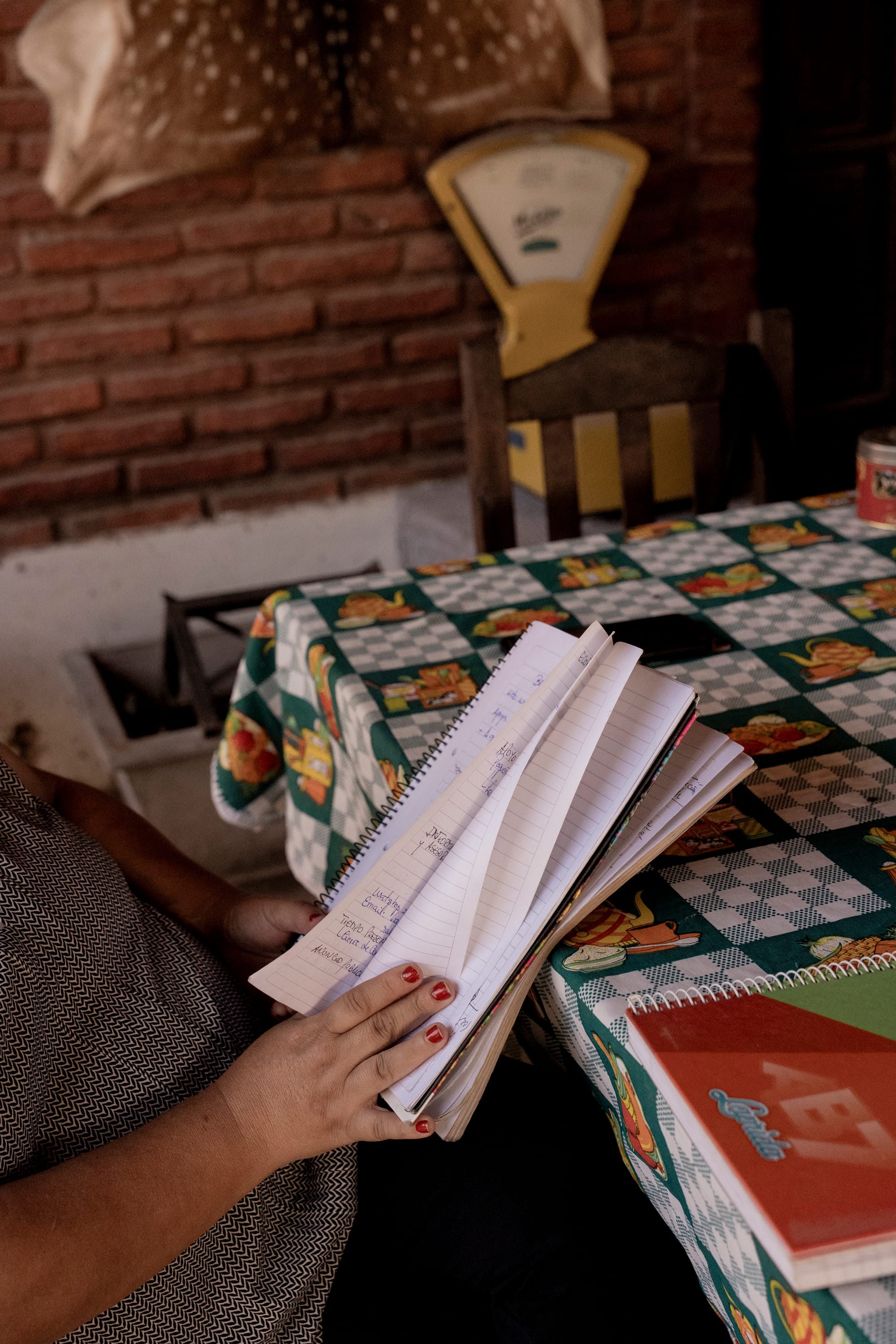

L: Mireya Gutierrez holds her notebook full of ideas and projects for her community at her farm on December 16, 2024, in Ifran, Goya, Province of Corrientes, Argentina. R: Cinthia Coria operating the mixing board during a broadcast of the radio program “Sapucai” on La Chicharra station on December 17, 2024, in Goya, Corrientes Province, Argentina. Photos by Anita Pouchard Serra with the support of the Pulitzer Center.

For Ojeda, both the school and her dispatches from the field for the radio program turned her into a local leader. Ojeda’s knowledge of the land was passed down to her by her parents, who were able to purchase their property in the early 1980s thanks to a government program that made agricultural plots available to rural families through an affordable payment system. In those years, they harvested mostly tobacco. Now she harvests a range of fruits and vegetables, turning pears and peaches into preserves that she sells at an artisanal fair she helped launch in a local town square.

In the mid-2000s she was a delegate for the province of Corrientes that helped draft new legislation that improved the conditions for family-run farms, giving them access to social security and other benefits.

But the progress has withered, she said.

Last year, Milei’s government closed the Institute of Family, Peasant, and Indigenous Agriculture, which helped small producers grow. At a press conference, the presidential spokesman dismissed the institute as a political patronage agency that had little to show for its two branches and 160 delegations under its purview. Roughly 900 positions were eliminated, leaving about 64, which Ojeda says has brought development and assistance to small producers to a standstill.

“We don’t get together anymore,” said Ojeda. “Everything has stopped.”

People such as Mireya Gutierrez are patching the gaps. She lives and works on a piece of land outside of Goya that she inherited from her parents. She and her brothers work the farmland and sell a range of crops at local fairs. But the seeds she is most interested in have to do with sowing opportunities for other rural families.

If you leave your place, you leave your history. You leave the legacy of your ancestors, who have built so much for you.

Sitting in their family garden, she pulls out a spiral notebook filled with notes she first began taking as a young community activist. Now 41, with a law degree and seasoned negotiating skills, she can point to the fruits of her labor around her. Internet service, for one. Even electricity. Basic services that the state did not extend to her stretch of farmland. Gutierrez has a knack for finding grants, loans, government projects, and other alternative funding sources offered through NGOs to secure money to build infrastructure. It takes creativity and diligence to find pots of money that can make a difference. On this day, she was contemplating how a call for environmental project pitches could help her community build a multi-use building. Improving infrastructure and access to services is not just a problem for today, but for tomorrow.

The main challenge, she noted, has to do with young people and their exodus from rural areas.

“Today, the human mindset is that I'll leave my place and go build somewhere else,” she said.

“If you leave your place, you leave your history. You leave the legacy of your ancestors, who have built so much for you. So you have to find a way not just to survive, but also to build.”

Governments may support the rural sector, but not the small scale producer, she clarified. “We’re the campesinos,” Gutierrez said. “The rural sector are the big landowners who live in the city but have their land and ranches here. That’s why the rural society is urban.”

She too attended La Chicharra’s gender studies school, and produced dispatches for the radio program. Cobbling money together from NGOs, she led workshops that gave women tools for adding value to their harvests by turning them into jams or other products—small initiatives that bring in much needed cash and build women’s sense of purpose and economic autonomy.

Ojeda credits the learnings she received and the sisterhood she found through the gender studies school as helping her get through difficult times. And she still leans on the practices passed down by her parents, focused on harvesting seeds, and then planting and protecting them.

“Sometimes we’ll give people seeds to take home, even if they haven’t brought anything to exchange,” she said. “We want them to produce their food, and for that to grow.”

This piece was edited by Nicole Froio and copyedited by Tina Vásquez.

This project was produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Natalie Alcoba is an Argentine-Canadian journalist based in Buenos Aires. She writes for numerous international publications including the New York Times, the Guardian, Al Jazeera, and the Globe and Mail. She covers a range of topics, including the women’s movement in Latin America, politics, and the economy.

Anita Pouchard Serra is a French-Argentinian photojournalist, visual storyteller and educator with a background in ballet dancing, architecture and anthropology, based in Buenos Aires and working between Latin America and France. Since 2017, Serra’s work has been published by the New York Times, Le Monde, El Pais and she has photographed personal projects on migration, identities, territories and cities, with the support of the Pulitzer Center and the Open Society Foundation. Serra is a winner of the 2024 GABO photography award and has displayed her work in international biennials and festivals. You can find her on Instagram and browse more of her work on her website.

“So…who are we canceling today?”

Subscribe to Cancel Me, Daddy, a Flytrap Media production, for the answer! Co-hosts, friends, and former Capitol Hill journalists Katelyn Burns and Christine Grimaldi discuss the latest developments in media and politics, providing thoughtful analysis and verbal shitposting you won’t find anywhere else. New episodes drop every other Thursday on YouTube and you can listen via Apple or Spotify. Be sure to check out the merch store—Merch Me, Daddy!

Catch up on our most recent episode—Democrats Were Banned From Saying These Progressive Words??. According to the center-left group Third Way, Democrats should scrub their vocabulary of 45 words and phrases spanning six pejoratively titled categories: therapy-speak, seminar-room language, organizer jargon, gender/orientation correctness, the shifting language of racial constructs, and explaining away crime. “Was it something I said?” Third Way asks of Democrats’ losing streak. No—winning is something you do. Campaign to victory on concrete policies that improve people’s lives! Join Katelyn and Christine as they cancel “Centrist Language Nannies” and the insufferable pundit class’s overhyped language policing.