Housing Haunts Me

If only getting a mortgage was as easy as opening a book.

Note: This post includes Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you buy books via these links, we receive a small commission.

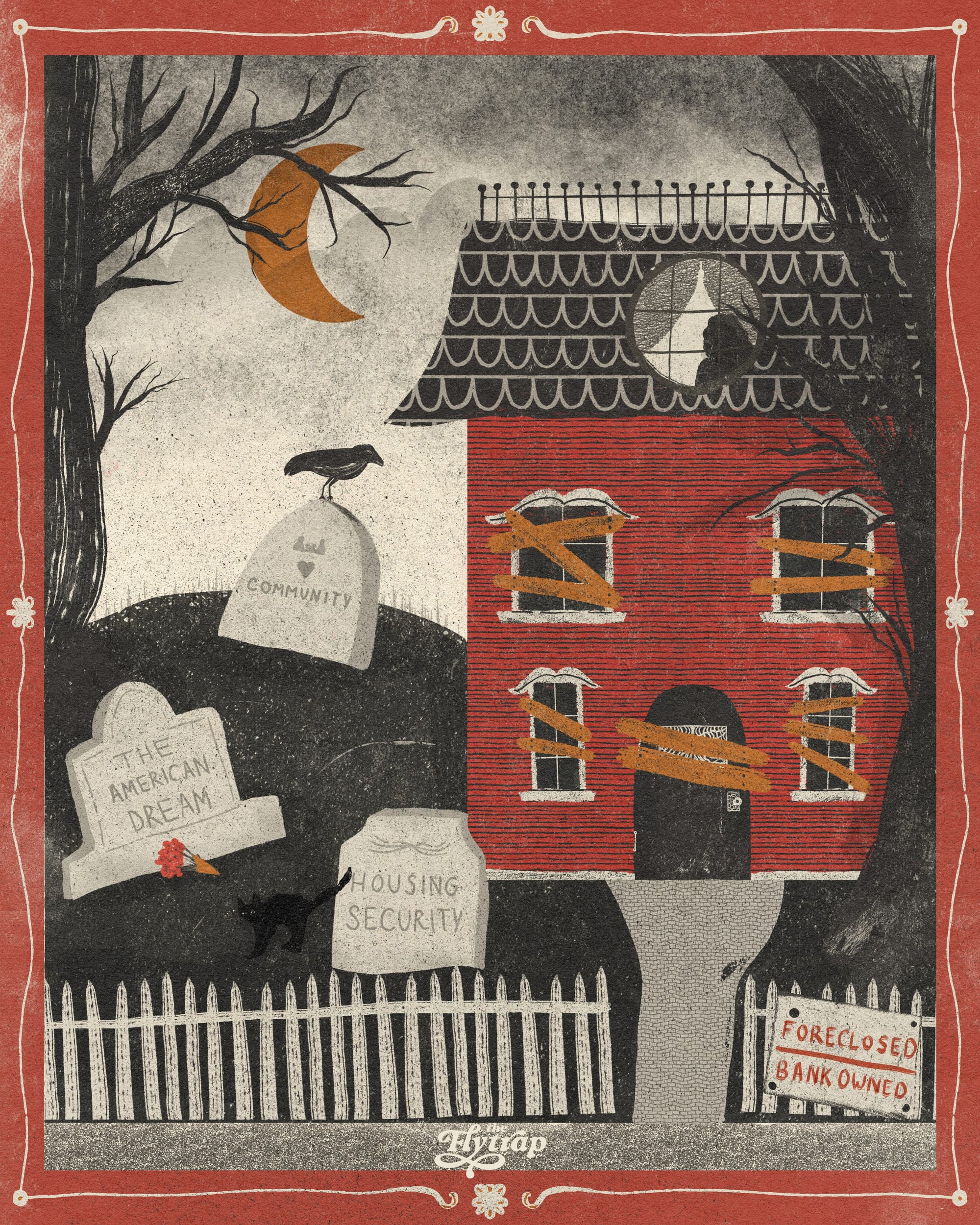

In 2008, my entire town slowly morphed into a realm of haunted buildings. Main Street turned rotting and gap-toothed as the recession claimed businesses and banks took the rest, while yard after yard sprouted “foreclosed” signs. Underemployed and wandering the streets, I saw an endless procession of “for sale” signage moldering in windows and watched the government bail out banks that were “too big to fail.” Meanwhile, my friends moved back into their parents’ houses, and George W. Bush turned an inherited Clinton boom economy into a quagmire with moves such as tax cuts for the rich and attacks on the regulatory state.

As an older millennial, I didn’t graduate directly into the recession, but it still had a profound impact on me. The 2008 recession shaped the trajectory of my career and the economic precarity that still looms over me and many of my generation. That economic precarity includes housing anxiety; in a culture where home ownership is treated as a sign of “making it,” and where making it is essential to being viewed as an adult, I’ve been a renter my whole life. There’s no realistic prospect of being able to own a home in the community I grew up in and returned to as an adult, and skyrocketing rents are making it extremely difficult to access housing stability.

Many within my generation, particularly those in BIPOC communities, are experiencing an intense sense of displacement where their homes and communities are snapped up as investment vehicles—rather than places where people live—and turned into short-term rentals and playgrounds for the wealthy. Gentrification has hollowed out once-lively, intergenerational communities of color from Oakland to Brooklyn and beyond.

Everyone is struggling. The entire country is in the grip of a housing crisis—there’s no state where people can afford rent on minimum wage. Housing occupies an outsized role in everyone’s mind, but there’s a particular flavor to millennial housing distress.

Housing haunts me, and haunted houses are clearly a larger cultural fascination.

I’m not alone in feeling a sense of hopelessness about the housing and rental market, and it isn’t a collective millennial hallucination: Our home ownership rates are lower than those of other generations, including Gen Z. Avocado toast and budgeting aren’t the problems here. The recession and the ripple effect it had on our earnings is. For every friend making a killing in the tech industry, I have 10 more eking out a living, scrambling to catch up. Some criticisms of millennial exceptionalism (as with any other generational exceptionalism) are warranted, but not at the expense of dismissing the economic, cultural, social, and physical legacy of coming of age into a global recession—the worst since the Recession of 1937-1938 (before you at me, pedants, I know there was a post-WWII GDP drop but the circumstances were a little complicated and driven by a drop in government spending that goosed the numbers).

When I say that I have a sense of existential dread about housing and my future on a nearly daily basis, I am not exaggerating. Housing haunts me, and haunted houses as a larger phenomenon are a bit of a personal obsession. Hauntings, especially of houses, are also clearly a larger cultural fascination. Classically, haunted house texts build on the deep legacy of Gothic novels, many of which were written by women like Mary Shelley, Ann Radcliffe, Daphne du Maurier, Emily Brontë, and others who were chafing at the confines of society’s expectations and beliefs. These stories have always been an essential part of the literary canon, but their framing and language tends to shift with the times to meet new generations of readers. Today, the legacy continues in the tone of a modern cohort of books about hauntings, whether from publishing houses that focus on horror or the much-vaunted shelves of “literary fiction” (a term that primarily seems to serve as a distinction between “real books” and “genre fiction”).

Notably, there’s been a recent growth in queer and trans horror that explicitly explores the experience of living in a marginalized body. These newest genre iterations not only push the idea of what it means to find a home in a terrifying house, but also explores how to find a home in a rejected, hated, feared body, and how to emerge proudly embracing and celebrating that body. Queer body horror—see Gretchen Felker Martin’s Manhunt (Nightfire, 2022) or Sarah Gailey’s Spread Me (Nightfire, 2025)—also explores this sense of being haunted in our own bodies.

There’s something unsettling, creepy, and destabilizing about thinking of the site of home as a site of fear or even evil; this place you think of as secure and safe is suddenly not.

Trans author Alison Rumfitt, for example, pushes at queerness and haunting in Tell Me I’m Worthless (Nightfire, 2023), braiding supernatural body horror with the very real horror of existing in a transphobic society. The main character, Alice, revisits a haunted house she spent a terrifying night in with friends three years before. Now, one of those friends has become a leading TERF, attacking Alice’s very right to exist, and the two are thrust together to figure out what really happened to the last member of their trio. Tell Me I’m Worthless is gory and shocking, referencing and challenging society’s treatment of trans people as monstrous and cartoonish.

There’s something unsettling, creepy, and destabilizing about thinking of the site of home as a site of fear or even evil; this place you think of as secure and safe is suddenly not. The place where you raise children and entertain guests turns hostile. Yet it’s also weirdly comforting to step outside my real, physical, and immediate housing anxiety and into validating territory: It’s not just your (or my) imagination. A house itself can become a malignant entity, one that may feed off you and literally consume you.

The disruption of sense of place and the instability that comes with this trope pairs incredibly well with a sense of “be careful what you wish for” and a streak of schadenfreude for members of the landlord class who bite off more than they can chew with their purchases. Oh no, did the house you bought to paint grey and flip come to life? Were you tragically and violently killed by an angry or hungry ghost? Were you forced to return to your family home and reckon with your father’s serial killing legacy, as Vera, the protagonist in Sarah Gailey’s Just Like Home (Tor, 2023), does?

At the same time, the haunted house genre also takes people through a familiar and reassuring trajectory. Typically, these stories end with a resolution, which is something I desperately seek in my own life—some kind of end point to this constant, sometimes overwhelming burden. The ghost is exorcised. The house and the haunting are destroyed. The main character realizes that they have frightened themself into a haunting and can make their own way out of it. Or perhaps the ghost turns out to be friendly, once the reason for the haunting is addressed, as seen in It Was Her House First (Poison Pen Press), Cherie Priest’s 2025 book about a series of people making terrible choices and a mother’s fervent desire to be heard. This classic friendly ghost shows up repeatedly: see Cordelia (Charisma Carpenter) and the murder victim Phantom Dennis (B.J. Porter), who turns into a kindly, even nurturing figure in her haunted Spanish Revival apartment in Angel (1999-2024).

DID YOU KNOW that we have a merch store!? You can support independent feminist media AND get some extremely cool art, such as this incredible poster from Nicole Froio's "'DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS' is Bad Bunny’s Latest Decolonial Text," itself an exploration of what it means to watch the place you call home deconstructed around you for someone else's gain.

Some haunted houses are marked by grotesque horror, including body horror, and extreme violence. Others are more whimsical and charming. Some are psychological thrillers. Occasionally the house itself is its own character with agency, not just an object occupied or manipulated by a ghost. This last category is perhaps the most intriguing for a generation that has experienced housing—or lack thereof—as the main character in their own lives.

In Nothing But Blackened Teeth (Nightfire, 2022), author Cassandra Khaw takes readers to a deeply creepy abandoned house in Japan, where a ghost bride stalks a wedding party. Khaw’s chilling and evocative language escalates fear and tension as the characters navigate a terrifying landscape and make disturbing choices in a home that seems to shift and shimmer through different realities. In Build Your House Around My Body (Random House, 2022), Violet Kupersmith takes readers through a fever dream of hauntings, loss, and the legacies of colonialism with a series of intergenerational disappearances and repeated mistakes surrounding a haunted rubber plantation. Trang Thanh Tran explores similar themes around the legacy of colonial violence in She Is a Haunting (Bloomsbury, 2024).

The haunted house is a deeply political metaphor, often a confrontation of our fear of the past—and our attempts to erase and sanitize it.

With Mapping the Interior (originally published in 2017 by Tordotcom and reissued by Nightfire in 2025), Stephen Graham Jones similarly uses a haunting to explore Indigenous experiences, colonialism, and identity through the lens of a child trying to literally map the house he inhabits, and by extension, to understand both personal and cultural loss.

The haunted house is a deeply political metaphor, often a confrontation of our fear of the past—and our attempts to erase and sanitize it. When Opal, a woman trying to escape poverty, takes a caretaker position in the uncanny titular mansion in Alix Harrow’s Starling House (Tor, 2024), the house turns out to be much larger and much more terrifying on the inside, itself a manifest character that carries a tremendous weight and history. Harrow’s exploration of poverty and the influence of the coal industry in Kentucky also explicitly takes on the history of slavery and its profound intergenerational impacts.

“I think what I wanted to say about class and poverty is that poverty is a form of violence and horror in and of itself, and that those experiences do emotional and physical harm,” Harrow told NPR in 2023. It’s an idea that resonates deeply with me as someone who grew up very low-income in a highly class-stratified community.

In an era overshadowed by the explosive and horrifying growth of “artificial intelligence,” horror authors are also rising to the occasion. A new crop of horror novels are exploring the realities of living in a world where AI is inserted into everything against our will, reflecting the sense of hopelessness and loss of control we may feel over our lives. In Rose/House (Tordotcom, 2025), Arkady Marine’s titular house is itself a character charged with keeping the records and legacy of architect Basit Deniau intact. When the house reports a dead body that shouldn’t be there—because it is only supposed to be open to one person, who is very much alive—it sets off a cascade of events that challenge what it means to humanize machine minds. Similarly, S.A. Barnes brings readers into the space age with a haunted ship in Cold Eternity (Nightfire, 2025), which features glitchy AI constructs and a grotesque monster feeding on people who thought themselves safe in cryostorage. In the world of Cold Eternity, nowhere is safe, not even after death.

Like many of the houses it explores, the haunted house genre is much bigger, much heavier, and more complicated than it appears at first glance, a maze of broken rooms and vengeance, sorrow and resistance, familiarity and terror.

The idea of sinking into a sprawling, fantastical house is also explored in Erin Morgenstern’s The Starless Sea (Vintage, 2020) and Susannah Clarke’s Piranesi (Bloomsbury, 2021). While these books are not usually treated as horror, and the houses here may not be explicitly identified as haunted, they clearly tap into this literary heritage. We know what to expect from these constructs and the people (or creatures) who inhabit them on the basis of our familiarity with the haunted house, and these stories push at the edges of this genre. While not necessarily malignant, these confusing sites of ever stranger and more labrynthine exploration include deeply supernatural elements through unsettling and sometimes whimsical travels of the mind and spirit.

There is a reason why the haunted house persists a metaphor for comprehending the world around us. The haunted house and its flexibility and power as a metaphor is such a familiar and established reference point that it appears in nonfiction as well, as in the case of Carmen Maria Machado’s intense memoir In the Dream House (Graywolf, 2020), in which each chapter draws upon a literary trope, with the title itself reflecting the web of rooms—metaphorical and literal—that Machado encountered in an abusive relationship.

Like many of the houses it explores, the haunted house genre is much bigger, much heavier, and more complicated than it appears at first glance, a maze of broken rooms and vengeance, sorrow and resistance, familiarity and terror. It is just like home. Sinking into these imagined worlds, the constant drumbeat of housing stress calms, at least for a little while. At least, until I refresh Redfin to see a new parade of ever-unattainable houses and am reminded yet again that I cannot afford to stay in the place I think of as home.

This piece was edited by Evette Dionne and copyedited by Andrea Grimes.

You're still here! Want more like this in your inbox and instant access to our entire archive while you support independent feminist media?