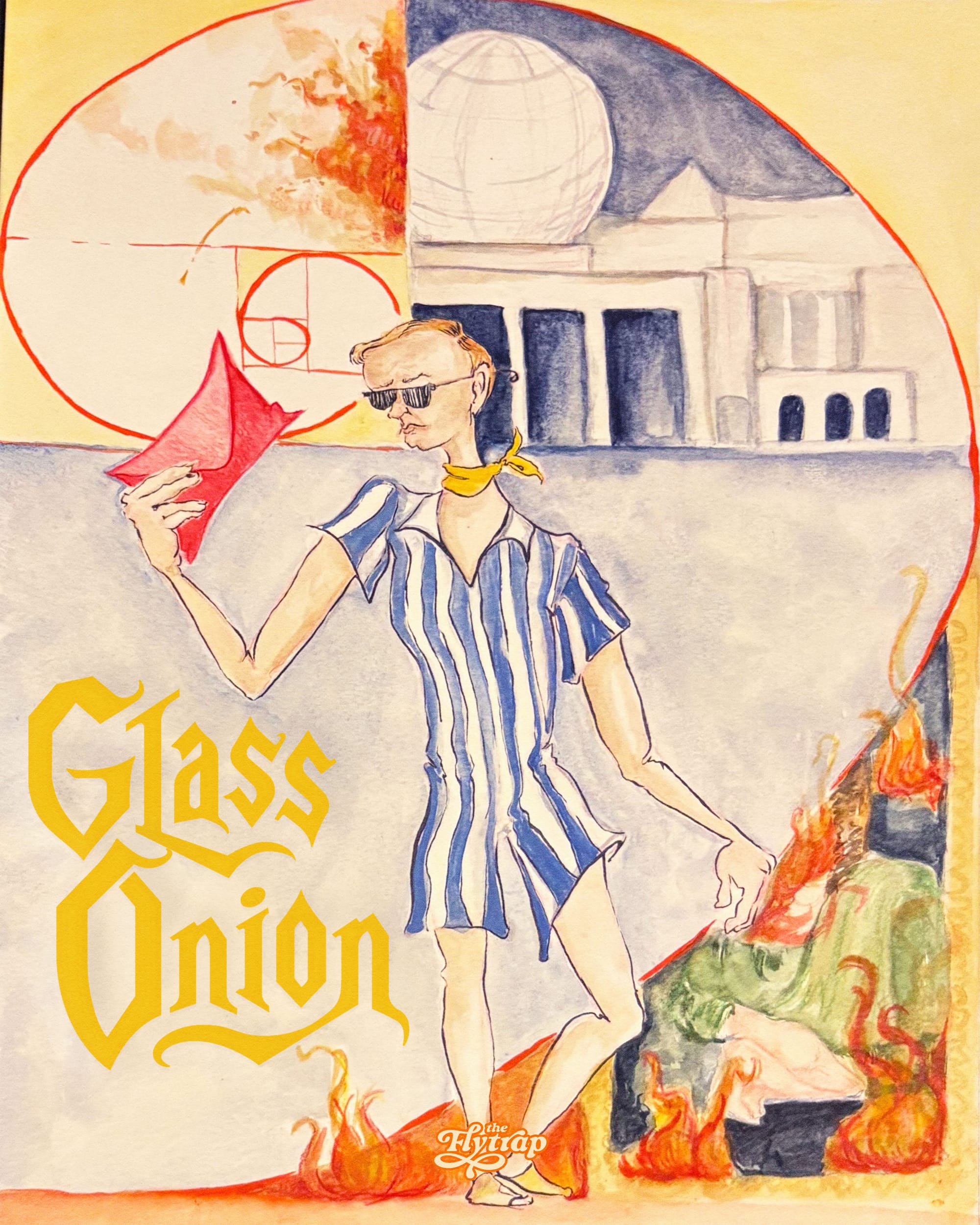

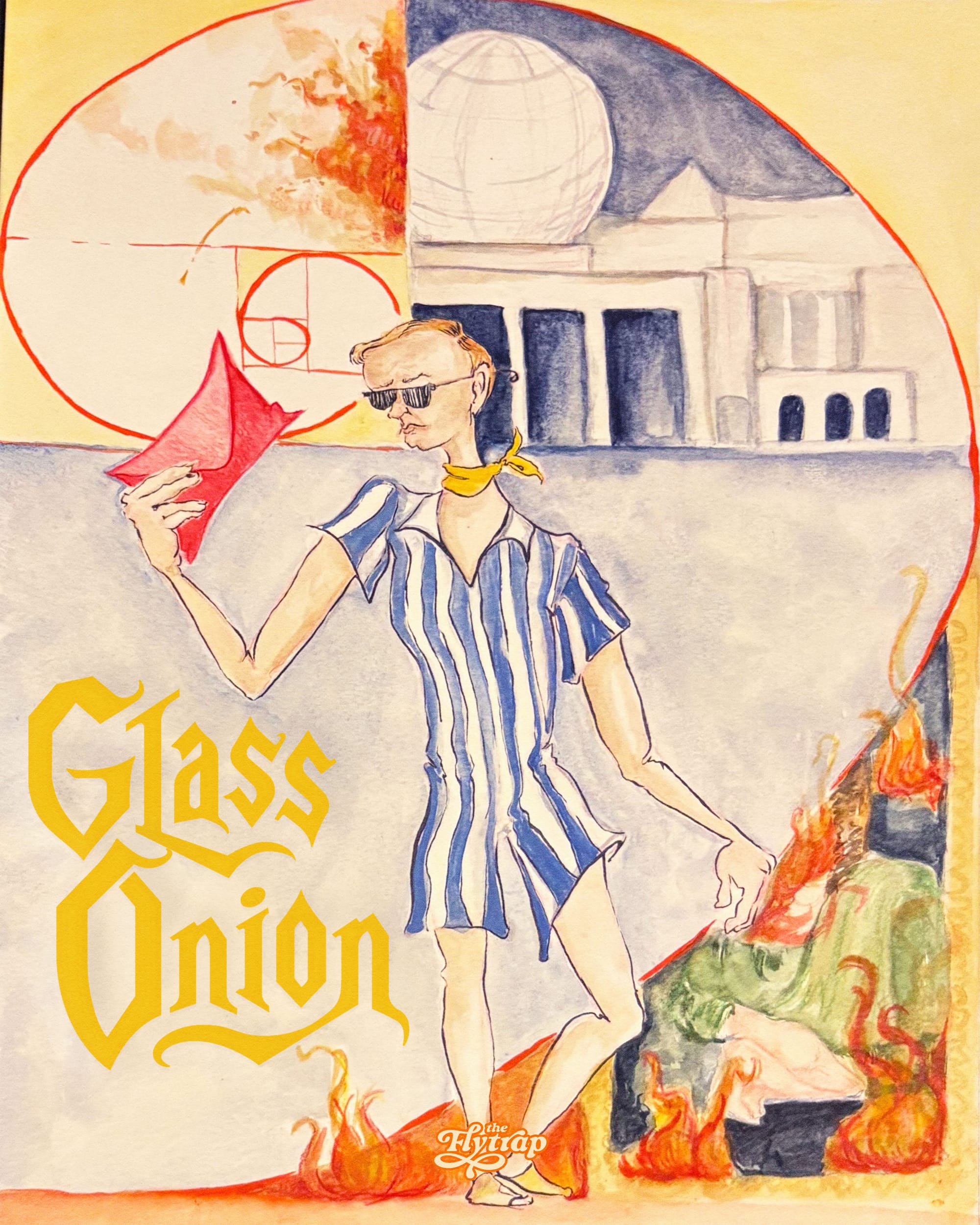

Peeling Back the Tech Broligarchy's Glass Onion

'Knives Out: Glass Onion’ skewered the tech industry. Three years later, the film remains an urgent call to reclaim entertainment and tech from the broligarchy.

'Knives Out: Glass Onion’ skewered the tech industry. Three years later, the film remains an urgent call to reclaim entertainment and tech from the broligarchy.