Fellas, Is Trash Praxis?

The greenwashing is coming from inside the house.

Sometime in late December, I discovered a vexatious problem at the grocery store: the plastic bags in the produce section had been replaced by thin, slimy, “compostable” bags that seemed primarily designed to make my produce go bad faster, in addition to being a sensory nightmare. After tossing some spoiled cilantro into the compost one evening, I threw an irritated post about my growing produce bag-related rage into the social media universe.

A commenter noted that the compostable bags reflected a new state law, SB 1046, which requires stores in California to replace petroleum-based plastic “pre-checkout” bags like those in the produce section with plastic-adjacent products considered “compostable” per ASTM International Standards. The bill joined a long list of laws designed to cut down on wasteful single-use products from propane canisters to Styrofoam that spend a brief time in the hands of consumers, followed by years in landfills.

These laws are often wrongheaded for a variety of reasons. Single-use products are not great for the environment, but the alternatives manufacturers brag about aren’t always better. Those bags, for example, require high-heat industrial compost, aren’t accepted by all composting companies, and wind up producing methane in landfills.

They also don’t address the underlying problem: It’s capitalism—not how my vegetables are bagged.

Capitalism is inherently wasteful because in order for it to work, people must buy things, including “services” and “consulting” related to buying and selling things. Capitalism also heaps waste upon waste with downstream waste that is itself spun into profits. If we want to make a meaningful difference in this situation, we need to address this highly lucrative secondary waste stream, not drink from single-use cups made out of corn while watching reruns of Captain Planet.

The bosses will profit whether you get paper or plastic or “plastic” at the grocery store. And since it’s easy to upcharge “environmentally friendly” products, companies can actually increase their margins! This can lead to greenwashing—using labeling and marketing to mislead consumers into thinking they are making a sound environmental choice that’s worth the extra cost. Capitalist forces use this messaging very effectively to create secondary markets for waste—and sometimes even to make people think that they are saving goods from waste when they are not, as in the case of selling ugly produce.

Spoiler alert: It’s Russian nesting dolls of garbage all the way down.

You Cannot Compost Your Way Out of Capitalism

The tech industry furnishes a classic example of capitalism’s wasteful underpinnings: People need to replace their computers and phones frequently, thanks to planned obsolescence—deliberately designing objects to fail early—and the pressure to keep up with the latest new thing. Apple profits when people buy new phones, so Apple is going to incentivize replacement—sometimes even with the offer of a trade-in. They’ll send a (recycled, of course) mailer to do it from the comfort of home, offering an old phone a second life and the buyer a warm and fuzzy feeling.

The old phone, meanwhile, enters the ewaste stream, which the World Health Organization estimates included 62 million tons of materials in 2022, making it one of the fastest-growing sources of waste worldwide. More than 22% of that was “documented” as recycled, sometimes “informally” with very unsafe conditions that can be incredibly environmentally destructive and particularly dangerous for children. Recycling electronics doesn’t involve progression through a magical series of steps performed by robots: Much of the work is up close and personal, dirty, requiring real human hands to dismantle and handle components.

The waste (limited actual recovery of components) of the waste (the old phone) looks like wishcycling, a term originally coined to describe the fact that many of the things you throw in your recycling bin are not recyclable. Thanks to murky labeling, unclear directions from recycling companies, and, sometimes, a little laziness, people throw garbage—sometimes garbage that will contaminate recycling—into recycling bins, with manufacturers well aware of this and happy to ship our “recycling” overseas, out of sight out of mind, for someone else to deal with.

If we want to make a meaningful difference in this situation, we need to address this highly lucrative secondary waste stream, not drink from single-use cups made out of corn while watching reruns of Captain Planet.

Wishcycling and the like generate profits, though not for the people and communities exploited in the process. In these cases, that downstream waste isn’t visible to consumers, while companies get undue credit for being “eco-friendly.”

Sometimes manufacturers engage directly with the waste in their supply chains and pitch you, consumer, as the solution to that waste, thereby making wasteful practices profitable while dodging the question of whether said industry should exist at all. The carbon credit and capture industry is one example: instead of extracting and burning less oil and gas, let’s just sell carbon credits and install massive, environmentally questionable carbon capture systems. Similarly, companies market textile recycling as a solution to fast fashion and the millions of tons of garments that end up in landfills every year, when a better question might be whether we could produce fewer, higher-quality textiles in addition to recycling.

The greenwashing element here is important, showing how companies cloak their practices in marketing to help people feel good about themselves while still allowing them to keep consuming. This reinforces the idea that consumers are the responsible parties here, not manufacturers, and that they should spend money to save our slowly-roasting planet.

Haste Makes Waste

Some consumers are smelling a rat as they start to notice that the people pushing “consumer responsibility” often have a business interest in doing so. Unfortunately, their pushback often still keeps the focus on consumers, rather than the structures around them.

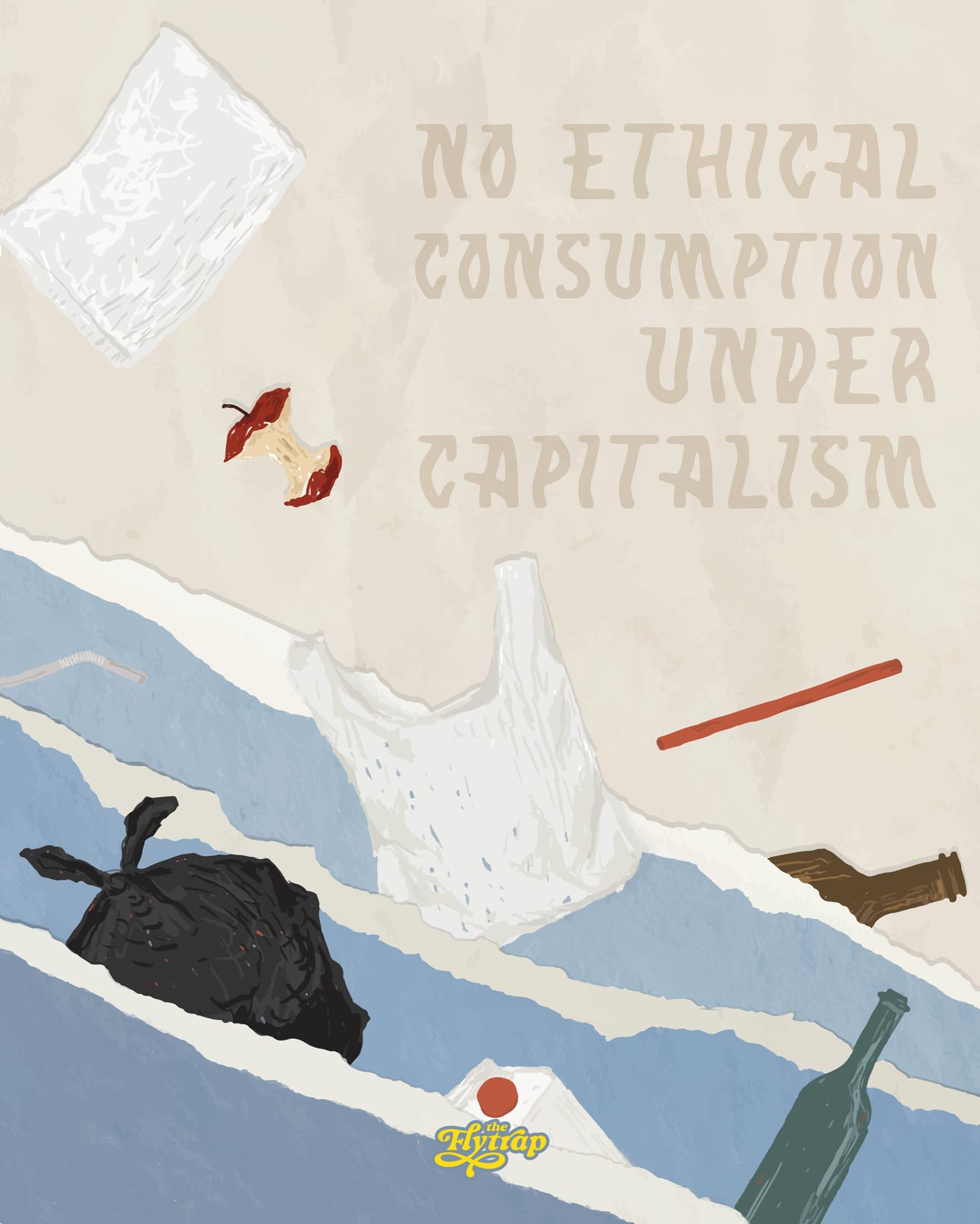

Discussion around “no ethical consumption under capitalism” is a popular topic on social media, but people tend to interpret the phrase in a way that means “everything is terrible, so I’m going to do whatever.” Let that trolley go where it may, we’re all fucked. Get yourself a little treat, nothing matters. There’s literally nothing I can buy that isn’t touched by Nazis and slavers and hatemongers, do you want me to just go naked?

Nothing I can buy.

If buying things is bad, perhaps we can turn not buying things into a virtue, goes a counter-argument, implying that the non-buyer has stepped outside capitalism and these exploitative systems. If you absolutely must buy things, of course, they should be organic/local/whatever ethical buzzword is “in” this week so you can lead a low-impact lifestyle with a reduced carbon footprint—a term popularized by the oil and gas industry to deflect attention from their ruinous practices.

The focus must stay on industry, holding businesses accountable for excess and even challenging the inherent validity of some industries. This is an institutional problem, not a personal one, and it requires collective solutions.

Maybe it’s not you buying things that’s the problem, it’s someone else. Conversations about consumer responsibility often single out specific groups as subjects of condemnation. Disabled people, for example, are scapegoats in Plastic Straw Discourse and in larger conversations about “waste” that revolve around disabled people as a drag on society. Women do the buying for the household, and are therefore to blame when purchases are not sufficiently virtuous. Poor and working class people who purchase items because they want to enjoy things, or for the purpose of class signaling, to show they are clawing their way through the capitalist project, are wasting money on useless stuff. Why do unhoused people have cell phones, conservatives like to ask, ignoring these products’ ubiquitous role in society and the fact that they have become a functional necessity to do things such as apply for jobs and housing.

Anticapitalism Is Inherently a Feminist Project

Who pays when we don’t address the problems of capitalism? Those most at the margins and least able to have an impact, exploited by organizations and systems around them. These communities are only further beaten down when people want to hold them personally responsible for melting ice caps because they use disposable menstrual products or sometimes forget to finish their leftovers before they go bad. Getting at the waste inherent to capitalism is one critical step that brings us closer to a world without capitalism itself, which makes this not just an environmental issue but a larger social one.

Since we do not live in a fantasy where it’s possible to wave a magic wand and replace capitalism with a flawless, ideal system with no possible downsides, how do we reckon with the waste problem? The focus must stay on industry, holding businesses accountable for excess and even challenging the inherent validity of some industries. This is an institutional problem, not a personal one, and it requires collective solutions.

Don’t get it twisted: Some consumer choices, especially when made with intentionality and care, are better than other choices. Individually, our actions can have an impact, sometimes in a profound way and especially on the local level. It’s also important, however, to avoid falling into the “something is better than nothing” or incremental progress logic, which allows wasteful systems to continue proliferating because people are too focused on consumer choices.

Consumers are better viewed in the aggregate, through their power as buycotters, early adopters, advocates for shifts such as a circular economy approach to manufacturing, and collective proponents for abolishing exploitative industries altogether. Consumers with more purchasing power, such as procurers for large corporations, can be in a position to force industry shifts, by for example, pressuring industries to invest in more ethical means of production, or advising their companies to stop purchasing products that do not actually need to exist.

There’s an added regulatory element: a world in which it’s harder for companies to dodge responsibility makes the waste stream very public. However, regulations can backfire. California’s Proposition 65, initially designed to alert consumers to the presence of carcinogenic chemicals, is a great example of a labeling law that generates so much noise, it's effectively useless; nearly every business I enter or product I buy seems to have a Prop 65 warning now. Similarly, the requirement to disclose sesame on labels has led to an ironic turn of events in which companies are adding sesame to avoid trying to keep production lines free of the allergen.

There are other meaningful regulatory avenues to pursue, and not in the sense of performative environmental laws like California’s “compostable” bag requirement. Legislation focused on industry, rather than end consumers, can address some of capitalism’s excesses by making them so socially and monetarily costly that they aren’t worth it. Particularly at this moment, such work is likely only going to take place on the state and local level, though even California has been withdrawing some environmental regulations in anticipation of federal challenges.

Ultimately, we all as a collective society need to stop buying it, and not in the sense of individual purchases but the entire systems surrounding them, and the highly successful corporate messaging that makes us attack each other instead of the bosses. That means valuing experiences and intangibles over objects, and making it possible to live in a world where we don’t need a growing pile of accessories to be happy, or to function. We need to make waste—primary, secondary, tertiary, and beyond—as public, expensive, embarrassing, and problematic as possible, and we need to be able to dismantle industries that contribute nothing but harm.

For now, I’ll see you in the produce section, where yes, I am painstakingly reusing an increasingly ratty series of precious plastic produce bags because I would like my produce to last longer than 30 seconds in the fridge.

This piece was edited by Chrissy Stroop and copy edited by Evette Dionne.