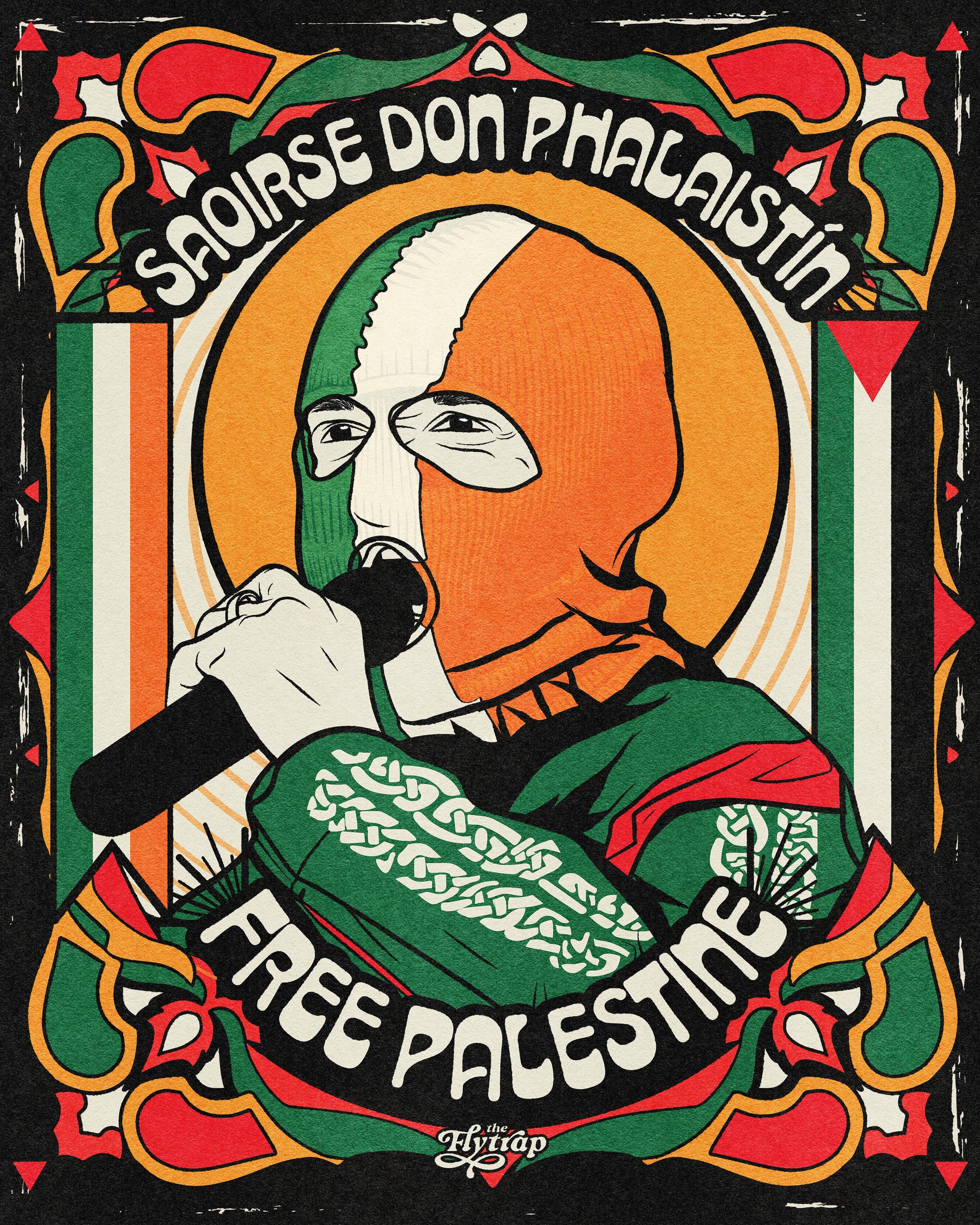

Censorship of Pro-Palestine Speech in the Music Industry Shows the Power of Demands for Decolonization

The liberation of Palestine is a threat to how we live today—that’s precisely why we should keep calling for it.

The liberation of Palestine is a threat to how we live today—that’s precisely why we should keep calling for it.